Proposal

Proposed Medals of Honor for Gettysburg

“The failure of the enemy to gain entire possession of our works was due entirely to the skill of General Greene and the heroic valor of his troops.”

- General Henry W. Slocum

Introduction

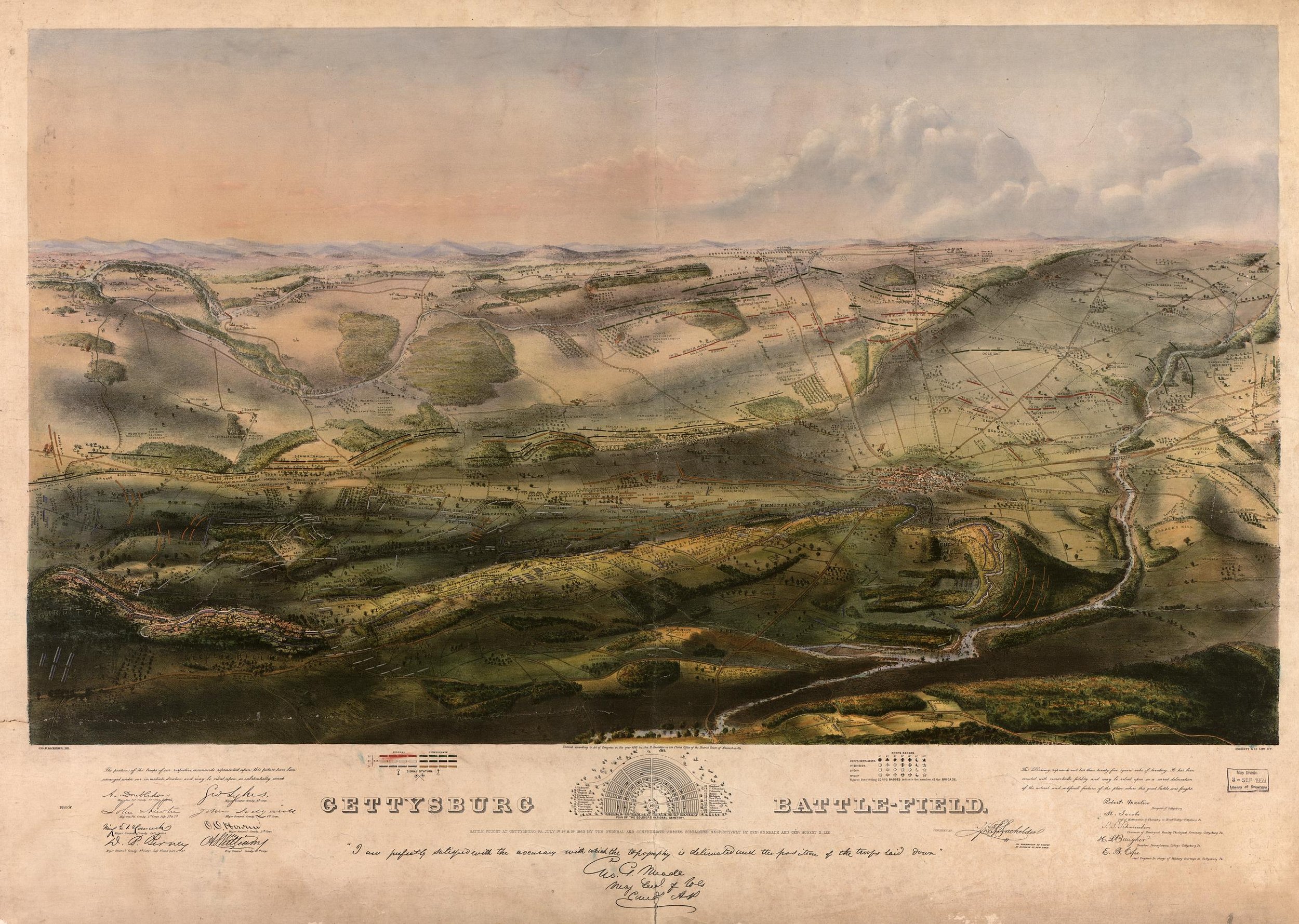

The XII Corps, commanded by Major General Henry Warner Slocum, played a decisive role in the defense of the Union right wing, on Culp's Hill, at Gettysburg, July 1-3, 1863. Yet, the officers and men of the XII Corps received no Medals of Honor. We are recommending several officers and enlisted men of the XII Corps for our nation's highest military honor.

The XII Corps was the smallest of the corps engaged at Gettysburg. Regiments from New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Ohio, Indiana, and Wisconsin were represented in the XII Corps.

The battle for the defense of Culp’s Hill is considered by many historians, past and present, to be the key battle for the Union victory at Gettysburg. For the past century, the battle for the defense of Culp’s Hill has been eclipsed by the battles for Little Roundtop and Pickett’s Charge on the afternoon of July 3.

After the battle of Gettysburg, General Slocum’s XII Corps was transferred to New York City to quell the New York Draft Riots in July 1863. As a result of this assignment, General Slocum’s reports and the reports of his commanders were received late by the War Department. This resulted in overlooking the men in units of the XII Corps in this all-important battle.

This document seeks to correct the 159-year-old omission of the awarding of Medals of Honor to deserving officers and enlisted men of the XII Corps and its supporting units.

This report includes all of the extant records from the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion (OR). It includes all of the Official Reports of the Army of the Potomac in the battle of Gettysburg and its aftermath. It also contains the official battle reports of the Confederate opposing forces that fought the XII Corps July 1-3, 1863.

Also included are memoirs and eye-witness accounts, both Union and Confederate.

This report was prepared by Eric Saul and Amy Fiske in tribute to the memory of the men of the XII Corps.

Gettysburg Battlefield

INFORMATION ON MOHS AWARDED FOR GETTYSBURG SERVICE

Prepared by Bill Endicott

The MOH was created in 1863, only 4 months before the Battle of Gettysburg. Thus, it was not as widely known then as it is today.

63 men received the MOH for actions at Gettysburg, but not one of them after having been killed in the battle. This is the case for most Civil War recipients. For some reason, unlike today, it appears that it helped a lot to be alive while the medal was being pursued on your behalf.

Furthermore, not a single MOH was awarded for action at Culp’s Hill, yet according to John Heiser, U.S. National Park Service historian at Gettysburg, the defense of Culp’s Hill was as vital to Union victory as was the defense of Little Round Top for which Joshua Chamberlain most famously got the MOH, or repelling Picket’s Charge, for which the most Gettysburg MOHs were awarded.

Only 19 of the Gettysburg MOHs (30%) were issued during the war itself, with all the rest of them being awarded in later years. In fact, 36 of them (57%), including the one for Joshua Chamberlain, were issued between 1890 and 1900. In other words, a long delay in awarding Civil War MOHs has always been the norm.

30 (48%) were awarded for picking up a flag or carrying a flag, or capturing a flag. (Andrew Jackson Smith who got his MOH in 2001 got it for this, which would not qualify under today’s more stringent criteria.)

16 were awarded to officers (25%), and only two of them to generals.

Major General Dan Sickles was awarded the MOH for encouraging his and other troops as he was carried on a stretcher to the rear while wounded. His citation reads: “Displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded.” But what is not recorded in the citation is that Sickles put his corps in a dangerous position and then scrambled to save it while under attack. As one officer put it, Sickles was lucky to have been wounded or he would have faced a court martial.

Brigadier General Alexander Webb is the other general to receive the MOH and his citation reads: “Distinguished personal gallantry in leading his men forward at a critical period in the contest.” Again, the citation does not do justice to the act, only in Webb’s case, what he did was even more heroic than the citation indicates. He personally rallied one regiment (71st Pennsylvania), attempted to lead one of his regiments (72nd Pennsylvania) in a counter-charge, then raced between the opposing lines to help rally another (69th Pennsylvania) in fear of losing their hold on the stone wall near the Angle. All of this involved the retaking of Cushing’s battery and the Union position at the Angle, which Webb was responsible for.

MOH recipient Colonel Joshua Chamberlain’s case is similar to candidate Colonel David Ireland’s case. Chamberlain’s citation reads: “Daring heroism and great tenacity in holding his position on the Little Round Top against repeated assaults, and carrying the advance position on the Great Round Top.”

On the surface MOH recipient Colonel Wheelock G. Veazey’s case might sound like Colonel David Ireland’s case. Veazey’s citation reads: “Rapidly assembled his regiment and charged the enemy's flank; charged front under heavy fire, and charged and destroyed a Confederate brigade, all this with new troops in their first battle.” But the difference is that whereas Veazey demonstrated exemplary personal leadership in front of an inexperienced regiment, and while exposed to enemy fire, Ireland’s command had enough experience to not require him to act in the fashion Veazey did.

MOH recipient Major Edmund Rice’s case sounds like candidate Captain Joseph H. Gregg’s case, except Gregg was killed and Rice was not. Rice’s citation reads: “Conspicuous bravery on the third day of the battle on the countercharge against Pickett's division where he fell severely wounded within the enemy's lines.”

MOH recipient Captain William E. Miller’s case sounds like candidate Captain Joseph H. Gregg’s case, too, again except that Gregg was killed. Miller’s citation reads: “Without orders, led a charge of his squadron upon the flank of the enemy, checked his attack, and cut off and dispersed the rear of his column.”

CHANGING CRITERIA FOR RECEIVING A CIVIL WAR MOH

Prepared by Bill Endicott

A total of 1,522 MOHs were awarded for Civil War Service, 1,198 of them for Army service.

During the Civil War, the MOH was not only the highest medal for valor, it was the only medal for valor. Consequently, it was often awarded for actions that would not qualify by today’s standards. (There were, however, other ways of honoring heroic actions that do not exist today, such as giving a man a higher “brevet rank,” in other words, a rank that existed in title only, but did not entail the pay or pension rights of the higher rank).

Furthermore, the application process was much less formal than today. Basically, you wrote the Secretary of War asking for the MOH, maybe submitting letters from witnesses to buttress your claim and maybe not.

Initially, the MOH was viewed with a certain amount of skepticism because it smacked of European practices that Americans were trying to get away from. In later years, however, when recipients noticed that they gained a certain amount of prestige in their communities for winning the MOH and were asked to lead parades and such, more and more men applied for it.

This accelerated until it reached the point where more than 700 men applied for it retroactively between 1890 and 1900 alone and 683 got it – an acceptance rate of more than 90%.

This caused President McKinley in 1897 to direct the Army to establish tighter policies regarding the application and award procedures. These were tightened still further in 1917, when 911 people, or about a third of those awarded up to that time, were “purged” from the official list. After that, today’s much more stringent requirements were more or less in place.

The result is seen in the statistics. Of all the 3,473 MOHs ever awarded, 1,522 or 44 % were awarded for Civil War service, even though many more soldiers have served in all the wars since then. For example, about 16 million men served in WWII alone, about 5 times as many as served in the Union army, but only 462 MOHs were awarded for WWII. So, it’s obvious that since WWI, it has been much harder to get the MOH.

FOUR CASES OF RECENT MOH APPLICATONS FOR CIVIL WAR SERVICE

Prepared by Bill Endicott

There have been four cases in the last 21 years, one involving Andrew Jackson Smith, who actually got the MOH in 2001, two involving Philip D. Shadrach and George D. Wilson who did not get it in 2008, and a fourth involving Alonzo Cushing who seems poised to get it as of this writing.

What follows is a review of these cases, including in some instances interviews with people who worked on them and who speak about the obstacles that have to be overcome in order to get the MOH retroactively for a Civil War veteran.

ANDREW JACKSON SMITH (1843-1932). A runaway slave, he served with the Massachusetts 55th Regiment, and received an MOH in 2001 (the same time Teddy Roosevelt got his retroactively for San Juan Hill). At the battle of Honey Hill, Smith picked up not one, but two flags, after the color bearers had been shot and carried the flags through the rest of the battle. This was the most typical situation a man could get the MOH for in the Civil War.

Dr. Burt G. Wilder who had been the regimental surgeon for the 55th Massachusetts, began a lifelong correspondence with Smith in hopes of securing a MOH for him. Smith was finally nominated for the MOH in 1916, but the Army denied him, erroneously citing a lack of official records documenting the case. One story at time was that Smith's regimental commander, Colonel Alfred Hartwell, was severely wounded and carried from the battle early in the fighting. Thus, the story goes, he was forced to complete his after action report at home while recuperating from his wounds and didn’t know about Smith’s action. As we’ll see in a minute, though, Hartwell did write about it, but it took years to find what he wrote.

It has also been alleged that another problem was that in 1916 when the request for a MOH for Smith occurred it was a time of increasing racial prejudice. And just a short while later African-Americans were denied the right to serve as combat troops in the American army in World War I (although some -- the 92nd and 93d Division -- did serve in combat while attached to the French army).

Nevertheless, Smith’s two daughters, Caruth Smith Washington and Susan Smith Shelton, both now deceased, preserved some original documents pertaining to Smith’s life and military service.

Then, more recently, Andrew Bowman of Indianapolis, Indiana, Smith’s grandson, was determined that his grandfather should receive the Medal of Honor, and he spent several years collecting records, conducting research and working with government officials and a history professor at Illinois State University. Bowman wrote an account of “Andy” Smith’s life at http://www.coax.net/people/lwf/AJSMITH.HTM.

Finally, new records pertaining to Smith's service were found in the National Archives, where they had been since the end of the Civil War. One of these new documents, one written by the commanding officer, Colonel Alfred Hartwell, was quoted at the 2001 MOH award ceremony:

"The leading brigade had been driven back when I was ordered in with mine. I was hit first in the hand just before making a charge. Then my horse was killed under me and I was hit afterward several times. One of my aides was killed and another was blown from his horse. During the furious fight, the color-bearer was shot and killed and it was Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith who would retrieve and save both the state and federal flags."

Here, at long last, was undeniable proof of what Smith had done.

In order to get a retroactive MOH, among other things, Congress has to pass legislation waiving the time limit for applying. And in Smith’s case, Senator Dick Durbin (D-Ill) and former Rep. Thomas Ewing (R-Ill) were the ones who shepherded such a measure through Congress and President Clinton signed it into law.

Dr. Sharon MacDonald, then an Illinois State University professor (now retired), and Robert “Rob” Beckman, a Dunlap, Illinois high school history teacher were the ones who found Smith's service records in the National Archives and Colonel Hartwell’s report about Smith’s actions, and they pursued the case with Durbin and Ewing.

On January 16, 2001, 137 years after the Battle of Honey Hill, Smith got the medal. President Bill Clinton presented it to several of Smith's descendants during a ceremony at the White House.

The following is Smith’s MOH citation:

"The President of the United States of America, authorized by an act of Congress, March 3, 1863, has awarded in the name of the Congress the Medal of Honor to Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith, United States Army, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.

"Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith of Clinton, Illinois, as a member of the 55th Massachusetts Voluntary Infantry, distinguished himself on 30 November, 1864, by saving his regimental colors after the color- bearer was killed during a bloody charge in the battle of Honey Hill, South Carolina. In the late afternoon, as the 55th Regiment pursued enemy skirmishers and conducted a running fight, they ran into a swampy area backed by a rise where the Confederate army waited. The surrounding woods and thick underbrush impeded infantry movement and artillery support. The 55th and 54th Regiments formed columns to advance on the enemy position in a flanking movement.

"As the Confederates repelled other units, the 55th and 54th Regiments continued to move into flanking positions. Forced into a narrow gorge crossing a swamp in the face of the enemy position, the 55th color sergeant was killed by an exploding shell and Corporal Smith took the regimental colors from his hand and carried them through heavy grape and canister fire.

"Although half of the officers and a third of the enlisted men engaged in the fight were killed or wounded, Corporal Smith continued to expose himself to enemy fire by carrying the colors throughout the battle. Through his actions, the regimental colors of the 55th Infantry Regiment were not lost to the enemy.

"Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith's extraordinary valor in the face of deadly enemy fire is in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon him, the 55th Regiment, and the United States Army."

In speaking of the circumstances about Smith getting his medal, Rob Beckman has said:

"I will warn you that the process is a lot more political than most people imagine. Even with the strong case that we presented and the clear evidence of racial discrimination involved, we still had to move several times to break our case free from politically motivated hold ups."

It is not known, however, what evidence Beckman has for making these charges.

PHILIP G. SHADRACH AND GEORGE D. WILSON. These two Privates were part of “Andrew’s Raiders,” the 24 Union men who participated in the “Great Locomotive Chase” that occurred on April 12, 1862, and for which the first MOHs ever created were awarded. Of the 24 men involved, two were civilians and thus were not eligible for the MOH. Of the remaining 22, all received the MOH, except Shadrach and Wilson, who were among the 8 men the Confederates hanged as spies. 4 men received the MOH posthumously after being hanged and it’s unclear why Shadrach and Wilson were not added to that list. Some reports said that Shadrach was disqualified because he had enlisted under a false name.

Former Rep David L. Hobson (R-Ohio) introduced a bill to award these two the MOH but it did not succeed.

Why the two did not get the MOH seems odd especially in view of this report of the Judge Advocate General wrote about the incident to the Secretary of War, which included the following:

Among those who thus perished was Private Geo. D. Wilson, Company C, 21st Ohio Volunteers. He was a mechanic from Cincinnati, who, in the exercise of his trade, had travelled much through the States North and South, and who had a greatness of soul which sympathized intensely with our struggle for national life, and was in that dark hour filled with joyous convictions of our final triumph. Though surrounded by a scowling crowd, impatient for his sacrifice, he did not hesitate, while standing under the gallows, to make them a brief address. He told them that, though they were all wrong, he had no hostile feelings toward the Southern people, believing that not they but their leaders were responsible for the Rebellion; that he was no spy, as charged, but a soldier regularly detailed for military duty; that he did not regret to die for his country, but only regretted the manner of his death; and he added, for their admonition, that they would yet see the time when the old Union would be restored, and when its flag would wave over them again. And with these words the brave man died. He, like his comrades, calmly met the ignominious doom of a felon—but, happily, ignominious for him and for them only so far as the martyrdom of the patriot and the hero can be degraded by the hands of ruffians and traitors.

ALONZO CUSHING of Wisconsin. Cushing died at his artillery post helping to stop Picket’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. He commanded Battery A, 4th U.S. Artillery. Ironically, the First Sergeant who served with Cushing at the time, Frederick Fuger, was awarded MOH for the same action.

A number of internet sites and even at least one book claim that Cushing has already been awarded the MOH, but that is not true. It’s true that the Secretary of the Army approved the award in 2010 and even that the House of Representatives approved it the first time in 2012. But then the measure died in the Senate and the process had to start over again. It passed the House again in 2013 and this time it even passed the Senate. Now the only remaining obstacle is to have Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel sign off on it, which he is expected to do.

The Alonzo Cushing case is different from the Andrew Jackson Smith case in a few interesting ways. First of all, Cushing was killed at Gettysburg, so he wasn’t around to push for the MOH himself. Most men who got the MOH for Civil War service were alive when they got it (although some from the “Great Locomotive Train Chase were not). Secondly, Cushing was never married, so there weren’t descendants to push for him to get the MOH, either. And lastly, many people not related to Cushing have worked on this case for many years.

Margaret Zerwekh, in her 90s who lived on the Delafield, Wisconsin property once owned by Cushing's family, first started working the case by writing Wisconsin Senator William Proxmire in 1987. Her grandfather was a Civil War veteran, which was part of the reason she was interested. But according to online stories, all Proxmire did was insert material into the Congressional Record about the matter; he didn’t formally ask Congress to waive the statute of limitations for applying for the award, nor did he ask the Army to approve the award.

Zerwekh subsequently wrote letters to presidents, senators and congressmen, and was herself written up in the New York Times for her efforts.

Another thing that helped Cushing’s case was the fact that Kent Masterson Brown, a Kentucky lawyer, published a biography of Cushing in 1993 called “Cushing of Gettysburg: The Story of a Union Artillery Commander.”

Finally, in 2003, then-Senator Russell D. Feingold (D-Wisconsin), officially nominated Cushing for the MOH and was even successful in getting the Secretary of the Army, John McHugh, to approve it in 2010. But also in 2010, Feingold lost his re-election bid, so he couldn’t continue working on the case. But Senators Herb Kohl (D-Wisconsin) and Ron Johnson (R-Wisconsin) the man who had defeated Feingold, took up the case.

In 2012, the U.S. House passed a measure authorizing the MOH for Cushing, but it was blocked in the Senate by Senator Webb (D-Virginia), who said at the time: “ It is impossible for Congress to go back to events 150 years ago to make individual determination in a consistent, equitable and well-informed manner.”

Subsequently, U.S. Representatives Ron Kind, (D-Wisconsin) and Jim Sensenbrenner (R- Wisconsin), pushed waiving the statute of limitations in the House and they succeeded in getting the House to pass it as an amendment to the FY 2014 Defense Authorization bill on June 14, 2013. The Senate passed the bill, with the amendment intact, on December 20, 2013.

A staff member from Rep. Kline’s office explained that when Senator Webb blocked the Cushing provision, he requested that DoD write a report about how Medals of Honor retroactive to the Civil War are awarded. (His request for it was formally included in the Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 4310, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013. House Report 112-705, page 765). A copy of the report is in the appendix to this section.

Although the report is helpful in describing process, when it refers to criteria for determining eligibility for receiving Civil War MOHs retroactively it unfortunately does not explicitly state what those criteria are.

There is still one more step before Alonzo Cushing can receive his medal: Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel needs to sign off on it. After the Secretary of the Army signed off on it in 2010, then-Defense Secretary Leon Panetta signed off on it, too. But DoD is saying that now that Panetta’s gone and Hagel’s in, Panetta’s approval is not enough and Hagel needs to approve it, too It is expected that Hagel will sign off, however, although when is not certain.

Close observers to the case say, however, that one problem with the Cushing MOH is who it should be given to, with the normal requirement being that it should be given to a blood relative and so far, none has been identified.

Senator Ron Johnson (R-Wisconsin) and Senator Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisconsin, (202 224 5653) led the effort on the Senate side.

REPORT ON PROCEDURES

APPENDIX -- REPORT TO THE COMMITTEES ON ARMED SERVICES OF THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

ON

PROCESSES AND MATERIALS USED BY REVIEW BOARDS FOR CONSIDERATION OF MEDAL OF HONOR RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTS OF HEROISM THAT OCCURRED DURING THE CIVIL WAR

June 2013

Prepared By:

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense

Personnel and Readiness

Executive Summary

The Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) does not have any standing review boards for considering Medal of Honor (MOH) recommendations endorsed by a Military Department Secretary to the Secretary of Defense (SecDef). Each recommendation is reviewed based on its own merit against MOH award criteria at the time the action occurred to determine if there is proof beyond a reasonable doubt that the member performed the valorous action for which they were recommended. Each MOH recommendation is staffed by the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness for consideration by the SecDef. Prior to consideration by the SecDef, each MOH recommendation is forwarded to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for endorsement and is reviewed by the Department of Defense (DoD) General Counsel for legal sufficiency.

The Military Department Secretaries have well-established procedures for processing MOH recommendations, including those from the Civil War era, within their respective Military Departments. The processes and materials used by senior decorations and awards boards vary slightly by Military Department. The senior decorations and awards review boards serve in an advisory capacity to the Military Department Secretary, who is solely responsible for determining whether a MOH recommendation merits personal endorsement to the SecDef. Civil War era MOH recommendations are, and should be, rare. Prior to notification of a favorable determination of such a MOH recommendation pursuant to section 1130 of title 10, U.S. Code, great care is taken to ensure the recommendation is fully vetted in accordance with the procedures outlined in the body of this report.

The DoD submits this report on processes and materials used by review boards for consideration of MOH recommendations for acts of heroism that occurred during the Civil War to respond to the report request contained in Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 4310, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (House Report 112-705, page 765). Specifically, the conferees “direct the Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the service secretaries, to report to the Committees on Armed Services of the Senate and the House of Representatives, not later than 90 days after enactment of this Act, on the process and materials used by review boards for consideration of Medal of Honor recommendations for acts of heroism that occurred during the Civil War.”

Office of the Secretary of Defense

OSD does not have any standing review boards for considering MOH recommendations endorsed by a Military Department Secretary to the SecDef. Each recommendation is reviewed based on its own merit against MOH award criteria at the time the action occurred to determine if there is proof beyond a reasonable doubt that the member performed the valorous action for which they were recommended. Each MOH recommendation is staffed by the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness for consideration by the SecDef. Prior to consideration by the SecDef, each MOH recommendation is forwarded to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for endorsement and is reviewed by the DoD General Counsel for legal sufficiency.

The Military Department Secretaries are responsible for establishing procedures for processing MOH recommendations within their respective Military Departments in accordance with OSD guidance contained in DoD Manual 1348.33, Volume 1, “Manual of Military Decorations and Awards: General Information, Medal of Honor, and Defense/Joint Decorations and Awards.” Each Military Department’s established procedures include a review by a senior decorations and awards board. The processes and materials used by the boards vary slightly by Military Department. However, it is important to note that each senior review board merely serves in an advisory capacity to the Military Department Secretary, who is solely responsible for determining whether or not to endorse a MOH recommendation to the SecDef. The Department of the Air Force did not exist during the Civil War. Accordingly, this report focuses on processes and materials used by the Department of the Army and the Department of the Navy (Navy and Marine Corps) review boards.

Department of the Army: Processes and Materials used by Review Boards to Consider of MOH recommendations for Civil War Acts of Heroism.

MOH recommendations for actions performed by Union Soldiers during the Civil War have traditionally been initiated by a Member of Congress pursuant to section 1130, title 10, U.S. Code, “Consideration of proposals for decorations not previously submitted in timely fashion: procedures for review.”

The Army Decorations and Awards Branch, Army Human Resources Command (HRC), Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel (G-1), reviews each MOH request submitted pursuant to section 1130, ensuring compliance with governing DoD and Army directives. This includes ensuring the recommendation contains a signed MOH recommendation, eyewitness accounts, and other documents supporting the recommendation. For Civil War MOH recommendations, justification for award often includes salient documents from the National Archives and Records Administration, letters and personnel records from the Adjutant General Office, Historical Society information (for example, articles, journals, and historical markers), and other documents deemed pertinent to the recommendation. Only verifiable facts and documents from reliable sources are used to make determinations regarding MOH recommendations from the Civil War era.

Each MOH recommendation is then forwarded to the Commander (CDR), HRC, through the Army Decorations Board (ADB). It is important to note that the ADB is advisory in nature and has no authority to approve or disapprove an award. Army Decorations and Awards Branch and advises the CDR, HRC, accordingly. The CDR, HRC, reviews each MOH recommendation against MOH award criteria, taking into consideration the advice of the ADB. The CDR, HRC, based on authority delegated by the Secretary of the Army regarding MOH recommendations that are unfavorably reviewed by the ADB, may: 1) disapprove the MOH recommendation; 2) approve award of a lower-level decoration; or 3) forward the MOH recommendation to the Secretary of the Army. The CDR, HRC, must forward all recommendations favorably reviewed by the ADB to the Secretary of the Army for consideration.

Each section 1130 MOH recommendation, prior to being forwarded to the Secretary of the Army, is reviewed by the Army Center for Military History to ensure the accuracy and authenticity of supporting documents. Subsequent to the historical review, the MOH is forwarded to the Secretary of the Army through the Senior Army Decorations Board (SADB).

It is important to note that the SADB is advisory in nature and has no authority to approve or disapprove an award. The SADB reviews the MOH recommendation against MOH award criteria and advises the Secretary of the Army accordingly. Upon review by the SADB, the MOH recommendation is forwarded to the Army Judge Advocate General, the Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel (G-1), the Chief of Staff of the Army, and the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs, each of whom also advises the Secretary of the Army regarding the merit of the recommendation.

All MOH recommendations under section 1130 endorsed by the Secretary of the Army to the SecDef have been fully vetted and evaluated in accordance with the procedures outlined above.

Department of the Navy (Navy and Marine Corps): Processes and Materials used by Review Boards to Consider MOH recommendations for Civil War Acts of Heroism.

The Department of the Navy has not processed a MOH recommendation for acts of heroism performed during the Civil War for many years. The last Department of the Navy MOH awarded for actions during the Civil War was approved more than 96 years ago.

Department of the Navy awards for combat heroism must be based on the testimony of eyewitnesses. The current requirement is for at least two signed and notarized eyewitness statements attesting to the individual’s heroic act(s). Additionally, all award recommendations must either be initiated by the commanding officer of the recommended individual or routed via the individual’s commanding officer for endorsement. There are no standing waivers for any of these requirements; they apply regardless of the conflict or time period during which the act took place.

From the foregoing, it is apparent that as a practical matter it would be nearly impossible to meet the basic requirements for recommending a Civil War Navy MOH. However, in an exceptional case where evidence was discovered of a MOH recommendation previously initiated by the commanding officer of a sailor/marine, that recommendation would be processed in the same manner as all other MOH recommendations for previous conflicts.

A MOH recommendation for a previous conflict is first reviewed by the awards branch of either the Navy Staff (sailors) or Headquarters, U. S. Marine Corps (marines). The awards branch staff will ensure the recommendation package is complete and complies with policies and regulations. Of particular concern is that it include a summary of action describing the valorous act(s) in detail, a proposed award citation, at least two notarized eyewitness statements attesting to the valorous act, and only such additional documents or material (for example, action reports, final investigation reports, deck logs, and medical documentation), that provide factual evidence of the individual’s heroic act(s).

If the recommendation meets regulatory requirements, it is reviewed by either the Chief of Naval Operations’ awards board, or the Headquarters Marine Corps awards board, as applicable. These boards are advisory in nature and do not have authority to approve or disapprove an award. The award is then endorsed by the applicable Service Chief: Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC) for marines; Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) or Director, Navy Staff (DNS) for sailors. The Service Chief may recommend the MOH, approve a lesser award, or disapprove the award.

After endorsement by the CNO or CMC, all MOH recommendations are reviewed by the Navy Department Board of Decorations and Medals (NDBDM), which advises the Secretary of the Navy on awards matters. The NDBDM will recommend to the Secretary of the Navy that he either: a) favorably endorse the MOH and forward the case to the President via the SecDef; b) approve a lesser award in lieu of the MOH; or c) disapprove the recommendation outright (for example, no award will be made). Although only the President has the authority to approve award of the MOH, the Secretary of the Navy is delegated authority to disapprove a recommendation for the MOH (or award a lesser decoration). No one else within the Department of the Navy is currently delegated MOH disapproval authority, and therefore, once properly originated, all MOH recommendations are forwarded to the Secretary of the Navy for a personal decision.

Summary

The Military Departments and OSD have well-established processes and procedures in place for reviewing MOH recommendations, including those from the Civil War era. Civil War era MOH recommendations are, and should be, rare. Prior to notification of a favorable determination of such a MOH recommendation pursuant to section 1130 of title 10, U.S. Code, great care is taken to ensure the recommendation is fully vetted in accordance with the procedures outlined in this report.